Now let’s continue the discussion we started earlier about investing…

“Be fearful when others are greedy. Be greedy when others are fearful.”

Earlier we introduced stocks and bonds as well as mutual funds and ETFs. Let’s expand a bit more on these investments and introduce some important concepts to help understand the basics of investing money.

What are stocks?

As previously mentioned, shares of stock represent a small piece of ownership in a company. These shares are listed on an exchange where they can be traded with other people or companies. An exchange is like an electronic version of a street market. Stock originally comes from companies that “go public”, meaning they sell shares of their stock to institutions and individuals. They do this to raise money so they can grow their business.

You buy and sell shares of stocks through a brokerage account. It’s like a bank account but provides access to these exchanges where you can buy and sell stocks and other securities or investments. The brokerage account is also where you hold these positions.

Stocks have a “ticker” or identifier. Apple is “AAPL”, Nike is “NKE”, Netflix is “NFLX”. Sometimes they change. Facebook used to be “FB” but then the company changed its name to Meta and the ticker is now “META”.

You can only buy shares in companies that are public. Private companies that you might be familiar with, such as Bluestone Lane or Joe & The Juice, don’t have shares listed to invest in. Someday they might “go public” to raise money to expand, but for now, they are privately held.

How do you make (or lose) money in stocks?

If a company returns some of its profits to its shareholders, you’ll receive a dividend. For example, if you own 100 shares of AAPL and it pays a fifty-cent dividend per share, then you’ll receive $50. It will be deposited in your brokerage account.

Dividends are one way to make money investing in stocks but most people invest with the expectation for the stock price to appreciate. The price of a stock reflects what people in the market are willing to buy and sell it at. If the company is successful, grows its business, and earns more money, then people are willing to pay more for a share and the price will go up. This can be significant for a consistently successful company over the long term. For example, Apple’s stock is up about 70 times since they announced the iPhone in early 2007. You would have gained a lot more from the price increase than the dividends they paid along the way.

Big established companies that are very profitable but are not growing that much might be attractive for the opposite reason. Their price might move up or down a bit here and there but they pay consistent dividends so you earn good income from them. Some examples are energy stocks, banks, or large conglomerates like GE or IBM. In fact, now that Apple is so big, you might make more in the future from dividend payments than from the price increase, even though in the past it was a fast-growing stock.

What are bonds?

Bonds are a different way companies raise money. They are loans a company takes out by selling bonds to the public. These usually pay a fixed interest rate, called a coupon, so don’t have the price gain potential that stocks have but also are less risky since they have “seniority” over stocks. That means the coupon payments have to be made before they can pay out dividends to stockholders.

Companies aren’t the only organizations to raise money by selling bonds. Governments - federal, state, and local - will also sell bonds. Government bonds pay a lower interest than corporate bonds because they are safer - the government guarantees the payments (in most cases) so they don’t need to pay as high an interest rate to borrow money as a corporation does.

Is “cash” just, well, “cash”?

You will see also “cash” referred to as a type of investment. This doesn’t literally mean cash you’d keep in your pocket or in a savings account. It means cash-like investments that are essentially risk-free, such as short-term Treasuries. Since these are backed by the US government, they don’t have the risk of default or of not being paid back. They do earn interest, however, so are usually part of an investment portfolio.

“Don’t look for the needle in the haystack. Just buy the haystack!”

There are over 6,000 public stocks traded in the US and hundreds of thousands of corporate bonds available. Sifting through all of these to find good opportunities is an impossible task. There are professionals who will do this and pool them together into funds. Then instead of buying stock or bonds in an individual company, you are buying a share of the pool that may contain dozens or hundreds of different stocks or bonds.

Of course, these funds aren’t guaranteed to do any better than you might, and they also charge fees for the work they do so that takes away from your potential gain.

But there are also funds that don’t need to do any real work to pick their stocks. They just buy the same ones that are part of an index. So an S&P 500 fund just owns shares in the 500 largest US companies. Or a Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond fund owns roughly the 10,000 largest corporate bonds in the Bloomberg index. Since the fund managers are just using a published list to determine which stocks or bonds to own, they don’t need a big research staff and thus their costs are much lower and the funds have very low fees. When you invest in funds that track a major index, it’s like you are buying a very small piece of the entire economy.

Buying a number of investments or pools of investments is a form of diversification

Key Concept: Diversification

Diversification can be summed up as “don’t put all your eggs in one basket”. With investing, there is concentration risk when buying just a small number of investments. Something bad could happen to the company you are invested in and its stock could crash. It might lose its most important customer, or its products may have a flaw and need to be recalled, or maybe the company broke some laws and is being sued.

By spreading your bets across a larger number of investments, you reduce the impact of any one of those investments performing poorly for whatever reason.

Index funds or ETFs are an easy way to get the benefits of diversification without the added work of having to research and choose a number of different investments on your own.

We mentioned stocks, bonds, and cash earlier. Over the last 100 years or so, stocks have returned an average of about 10% a year, bonds about 5%, and cash about 3%. As we’ll soon see, in any one one year it can vary a lot, but those are pretty typical averages.

Since stocks have the potential to grow in price significantly, why not put all your money into stocks? Well, that introduces the concept of risk vs. reward or the risk-reward tradeoff…

Key Concept: Risk vs. Reward

Investments that have the potential for larger gains, also have the potential for larger losses. These large movements in the value of the investment over time reflect the risk in that security. Stock prices can move up and down dramatically over short periods of time based on economic news, company-specific news, or just the emotions of the people in the market. There is no “correct” price for a stock so it’s very subjective to gauge whether a certain stock is underpriced or overpriced.

Bonds, on the other hand, are loans with interest or coupon payments. You know what you are getting and you can calculate an appropriate price for a bond, to a certain degree. So the prices of bonds move around much less than stocks and are therefore considered less risky. But for that lower risk, they offer lower returns.

No free lunch

Here’s a chart of different types of investment classes or asset classes, showing their average long-term return and their risk, expressed in the typical annual percentage move (the standard deviation of their price changes).

You can see that to achieve higher returns you have to be willing to accept more risk, but note that the relationship curves downward and is not linear. That means the additional risk grows faster than the additional return so you have to be cautious about investing in high-return securities.

From this chart it might appear that you have only a few types of investment choices and none of them may be in the ideal spot on the curve where you would be most comfortable. But you can use a combination of different types of investments to achieve a mixed result that will fall somewhere else on this curve.

For example, if you choose to put 75% of your investments in Large-cap stocks and 25% in Corporate bonds, that portfolio would fall roughly on the curve between those two points, closer to the Large-cap point. This process of choosing different portions of your money in different types of investments is called asset allocation.

Key Concepts: Asset Allocation, Rebalancing, and Averaging

Asset allocation involves dividing your investment portfolio among different asset classes, most typically stocks, bonds, and cash. By including asset classes with returns that tend to move somewhat independently from each other, you help protect yourself from significant losses and your returns will also tend to be smoother over time, that is, the volatility of the overall portfolio will be lower.

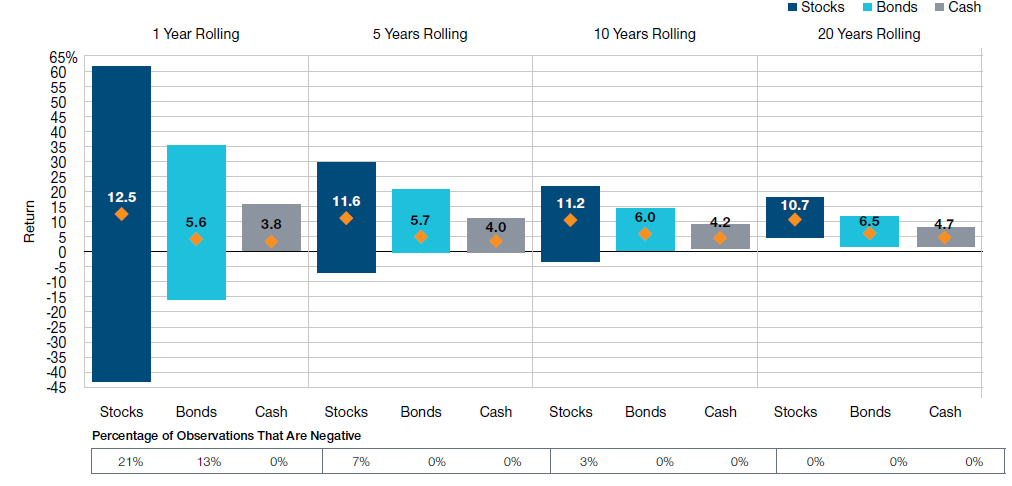

Asset class returns by holding period

Asset class returns by holding period

This chart compares the performance of different asset classes over the last 75-80 years across different holding periods. For example, the group on the left shows a one-year holding period, which means that in any one year, stocks—the dark blue bar—had returns that varied between up 62% to down 43% and averaged up 12.5%. One-year returns of bonds ranged between 35% and -16% averaging 5.6%, and the one-year return of cash (represented by a three-month Treasury bill) ranged between 15% and 0%, averaging 3.8%.1

But notice as you move to the right with increasing holding periods, the variability of the returns compresses while the average moves around just a small amount and we can see in the 20-year band that there were no cases where any of the asset classes lost money.

The important takeaway here is that for a long investment time horizon, you can ride out market downturns and in the long run will usually experience good returns. Patience pays off in investing.

But you can also see that if you know you’ll need some of your money sooner, then it’s going to be safer to put more of it in bonds and even cash.

Once you start following an asset allocation approach, you’ll need to make adjustments periodically to keep your portfolio on track. This is a process called rebalancing. Let’s look at an example to see why it’s necessary and how it works.

Rebalancing example

| Asset Class | Allocation Percent | Allocation Value | One-year return | End-year value | Target | Amount to add | Pct to add |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stocks | 80% | $40,000 | 12.52% | $45,008 | $48,000 | $2,992 | 59.83% |

| Bonds | 15% | $7,500 | -1.10% | $7,418 | $9,000 | $1,582 | 31.65% |

| Cash | 5% | $2,500 | 2.96% | $2,574 | $3,000 | $426 | 8.52% |

| 100% | $50,000 | $55,000 | $60,000 | $5,000 |

Let’s say you had a portfolio of $50,000 and 80% of your portfolio is in stocks, 15% is in bonds and 5% is in cash. That’s a pretty typical allocation for someone early in their career say in their 30s.

This table shows a hypothetical case if you had a return of 12.52% in stocks, -1.1% in bonds, and 2.96% in cash which works out to a total return of exactly 10% in the portfolio, thus a $5,000 gain.

Now you plan to invest an additional $5000 but you want to bring the new values in each asset class back to their target weights of 80%, 15%, and 5%, respectively.

Since your stocks were the best performer, the value of those holdings has outpaced the total portfolio (12.52% vs 10%) and thus you need to put less than 80% of the additional money into stocks. In this case, it’s about 60%.

The other two asset classes underperformed the 10% total return so you need to buy more than their target amounts. For cash, we need to buy 8.52% vs 5% and for bonds, we need to buy 31.65% vs. 15%. That’s because bonds actually lost a little money.

The net effect is that you are buying more of the cheaper asset classes and less of the expensive asset class. This helps your return over the long term because you are buying more of something when it’s cheaper and then over time when it goes back up (hopefully), you’ll compound your gain a little bit. This can make a real difference over many years.

One other concept of note here. When investing money, one thing people sometimes worry about is that they are buying something at the wrong time and that it might go down in price soon after they buy it. But that can lead to indecision and then you have just as much of a chance of the price moving up while you sit on the sidelines, and now if you invest you’ve bought the investment at a higher price.

The best approach is to take a long-term view and not worry so much about the short-term up and down movements. And if you are consistently investing money in the market each month, quarter, or year, then these ups and downs will average out. This process of investing regularly over time is called averaging and the benefits of this approach are that it will smooth out your investments over time, plus you will end up buying more shares of an investment when prices are lower so it has a very positive impact when investing through recessions and “bear” markets.

Asset allocation, rebalancing, and averaging go hand-in-hand when investing.

We’ve covered a lot of details about investing. Let’s now wrap all of that up into some straightforward advice in terms of managing your investments.

Three investment approaches

Let’s look at three approaches to investing that build on the ideas we’ve discussed.

“The biggest risk of all is not taking one.”

In terms of investing, if you were to distill all the things we’ve discussed so far and implement the simplest approach that would require the least amount of time to manage, the recommendation would be:

Approach 1: Keep it simple

Put everything in an S&P 500 Index fund

- save 20% or more of your earnings each paycheck

- once a year, invest your excess savings (beyond your emergency cash fund) into a large equity index fund or ETF like SPY

- repeat year after year after year…

Putting 100% in the stock market might sound a little scary, but consider your situation. You are young, you have cash on hand, and shouldn’t need to dip into your investment portfolio, thus you can afford to take the most risk at this point.

This is the exact strategy that Warren Buffet recommended in his 2013 letter to shareholders. He said to put 90% in an S&P 500 Index fund and 10% in cash but since you will already have an emergency cash fund set aside, they are effectively the same thing.

Approach 2: Light touch

- Shift a small amount of S&P 500 Index fund into bonds

- 90% S&P 500 Index fund

- 10% Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index fund

A second approach, that requires only slightly more effort, is to introduce an asset allocation layer across stocks and bonds. In this model, you’d maybe put 90% in stocks and 10% in a large bond index fund or ETF like AGG. Then each year when you put your additional accumulated savings in, you’d split it up to reach that target allocation after adding in the additional money, like the previous example we walked through.

This is slightly more work but since you only need to rebalance once a year, it’s not a big deal. And it will get you more familiar with the practice of asset allocation, rebalancing, and averaging.

You can also shift from the first model into this model down the road, say in your 30s when you don’t feel as comfortable with 100% in stocks. Plus, you can expand this approach into other asset classes at that time, say real estate, commodities, or international equities.

You could stay with this model your entire life and as you get older and closer to retirement, just shift more of the stock allocation into bonds and also into cash, targeting to have maybe an allocation of 60% stocks, 30% bonds, and 10% cash near retirement.

Approach 3

Approach 3: Hands-on

- Shift a portion of S&P 500 Index fund into 3-5 stocks

- 70% S&P 500 Index fund

- 20% 3-5 individual stocks

- 10% Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index fund

The third approach is probably only something you’d consider if you really find investing interesting and want to spend more time and attention on it. You could set aside a portion of your portfolio to invest in a few individual stocks. You should start small, putting no more than a quarter of your portfolio and shifting it into 3-5 stocks that you are interested in. That’s enough to make a difference if one of them does really well but also small enough that if one of them crashes, it won’t set you back too much. Fewer than 3 stocks are risky because you’ll end up with too much money in one position. And more than 5 stocks start to become a lot of work to stay on top of them, plus the positions will be small enough that a big gain won’t have much of an impact on your overall portfolio.

This approach will require more time to keep up to date with the stocks in case something changes and you might want to reconsider the investment. You should review your portfolio each quarter instead of annually to see if any of the reasons you originally bought any of the stocks has changed, in which case you might want to sell a position.

With individual stock positions, there will be more ups and downs in your portfolio. It’s easier to get anxious and make a rash decision, which you want to avoid when investing for the long term. That’s why this approach isn’t for everyone.

I recommend starting with the first approach and then over time you can grow into the second and even third approach as you develop more interest.

-

https://www.troweprice.com/personal-investing/resources/insights/asset-allocation-planning-for-retirement.html ↩